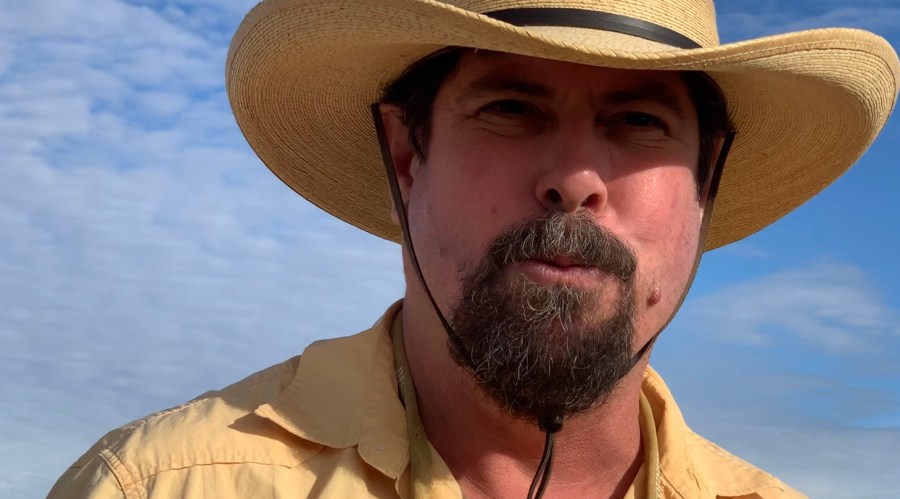

SAN BERNARDINO NATIONAL REFUGE, Arizona (Border Report) — Myles Traphagen, a Wildlands Network ecologist from Tucson, Arizona, can recite the names of most wild grasses, trees and animals that live in this remote region of southeastern Arizona.

He pulls blooms off the stalk of some cane beardgrass, (or Bothriochloa barbinodis) and shows how it leaves a blueberry-like smell on your hands. Or maybe lemonade.

“I think it’s blueberries,” Traphagen said Friday as he gave Border Report a tour of the San Bernardino National Refuge, which is about 10 miles east of the town of Douglas.

It’s an area he says is ecologically special because it is the “crossroads of the North American continent.”

These desert grasslands are the meeting point of four diverse ecological areas: the Rocky Mountains; the Sierra Madre Mountains, the Chihuahuan Desert and the Sonoran Desert. It is a lush desert grasslands valley where threatened animals like jaguars and the white-sided jackrabbit have been spotted, and it is home to the only native catfish west of the Mississippi River, the Yaqui catfish.

The first known jaguar crossed into the United States in 1996 over that mountain, Traphagen said pointing in the distance.

Traphagen, 52, has spent thousands of hours studying this region, first for U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and then later when he did his master’s thesis on the migration patterns of the white-sided jackrabbit, a nocturnal hare of which there are probably fewer than 100 living, he said.

But as he stared through binoculars from a ridge a six-block walk from the entrance to this national park describing their migratory patterns on Friday, he suddenly stopped mid-sentence and gasped.

A half-mile in the distance — in a valley adjacent to some artesian springs in an area called Blackwater draw, which are the headwaters to the Rio Yaqui — Traphagen first noticed a small segment of new border wall rising from the valley floor.

These are the first border wall panels built by contractors — hired by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — in this section of southeastern Arizona. And they are put in such a remote dip in the topography that they are almost not visible.

But follow the dust smoke that rises from an endless caravan of construction trucks and heavy equipment going to and from the site and the new border wall here suddenly becomes quite clear.

What isn’t quite clear to those not as familiar with this region as Traphagen, however, is the ecological importance of this area and the impact that the construction, the border wall, and the pumping of thousands of gallons of ground water to make the border wall concrete base, will have.

“They’re building a border wall and they’re mixing up tons of concrete every day. Since they don’t have to comply with any environmental laws or a construction plan they can just pump as much as they want. They don’t have to report that. So you wonder: What’s going to happen to the ponds and the native stream here at Blackdraw when they potentially pump all the groundwater out?” he said.

Altogether, 19 new border wall miles are planned to run through this area in Cochise County. And it comes as CBP is building miles of border wall on the southwestern side of the state in Organ Pipe Cactus National Wildlife Refuge, another national park.

Read a Border Report story on a protest held Saturday at Organ Pipe Cactus National Wildlife Refuge against the border wall.

President Trump has waived 41 environmental rules in order to expedite the building of the border wall, which he has said is necessary for national security.

Here at San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, construction crews are working around the clock, and as nightfall arrives, they bring out giant floodlights and transport them to the site so they can continue to build the border wall.

Middle of nowhere

The juxtaposition of these few new panels first spotted on Friday — possibly just six, but it’s hard to tell from a half-mile distance, and the construction area is closed to the public — is baffling. It is located just beyond a ridge of cottonwood trees that line Blackwater draw, at the base of several mountains literally in the middle of nowhere.

The bluff overlooking the valley even has mortar and pestle-like artifacts carved into the large stones. This is proof, Traphagen said, that ancient people lived and worked these hills “thousands of years ago.”

In order to get to this remote overlook bluff one must walk six blocks in the refuge down an unmarked dirt road lined with cholla cactus, ocotillo, kangaroo rat mounds, and the blueberry-scented grass.

Traphagen said he has spent thousands of hours here studying various species, like the threatened hare, and says he has gone weeks without ever seeing another soul. Several times he has been questioned by Border Patrol agents, he said.

But now 18-wheeler trucks rattle by down a dirt road that has been widened, and dozens of construction workers can be seen digging, operating heavy machinery, and extracting water from a staging area a few miles east of the wall construction site.

The beginning segment of the rust-colored, 30-foot-tall metal wall is visibly incongruent with the surrounding lush greenery in what Traphagen describes as a desert oasis.

This is where animals come for water as they head into or out of Mexico, albeit the animals have no idea they are crossing international lines. But soon they will Traphagen said, because they will be unable to breach the 30-foot-tall wall, and they won’t be able to access water or follow their natural migratory routes, and neither will their prey.

“That’s going to cut off the only migratory route for the white-sided jackrabbit between Mexico and the U.S. There is no other way it can enter the country that way and go back and forth between Mexico and the U.S.,” he said. “This could be the nail in the coffin for the species as it occurs in the United States now.”

Traphagen says Mexican ranchers should also be concerned because he believes the water levels will go down, and that means less water flowing south to their lands. “

I’d like to ask Mexican farmers and ranchers what’s going to happen to your springs when we’re in this groundwater basin and all of a sudden your springs go dry and then you have a landscape that can no longer support farming and ranching?” he said.

Behind one mountain, about 20 miles southeast of this very spot, is where authorities say warring drug cartels killed three American women and nine children recently who were all from a ranching family who travels to and from the United States.

Read a Border Report on the slain American women and children.

“What’s going to take over that economic niche? So when you think of this in an ecological context and then a human economic context, we are just throwing fuel on the fire here,” Traphagen said.