A whiteboard at a Los Angeles County jail tracks how many days since guards on this floor had to forcibly restrain anyone: 54.

Nearly a dozen young men are chained and handcuffed to shiny metal tables bolted to the floor.

“It’s lunchtime and they’re actually [in] programming right now,” says a veteran guard, LA County Sheriff’s Deputy Myron Trimble.

Programming means a treatment regimen. “I think everyone can agree that it’s rather inhumane to have the inmate handcuffed while out,” says LA Sheriff’s Capt. Tania Plunkett, with the Twin Towers’ Access to Care Bureau. “However, because of spacing and the lack of programming, we’re not able to really focus on getting the inmate better to eventually lead to having them in a program without being handcuffed.”

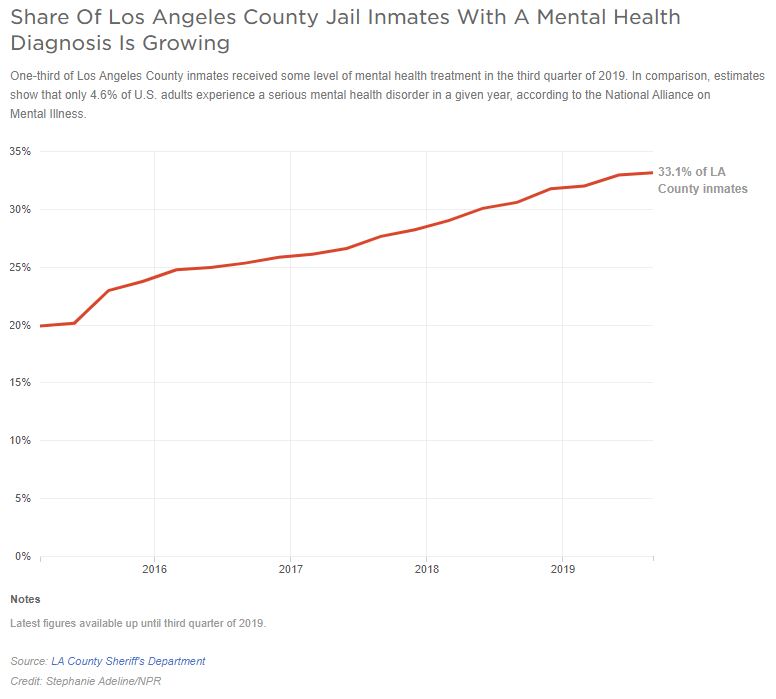

The LA County jail system now holds more than 5,000 inmates with a mental illness who’ve had run-ins with the law, according to NPR.

“When I started in 2013, mentally ill inmates were only housed on the seventh floor and the sixth floor right below it,” Capt. Plunkett says. “To date, the entire facility consists of mentally ill inmates.”

“By default, we have become the largest treatment facility in the country. And we’re a jail,” says Tim Belavich, the director of mental health for the Los Angeles County jail system. “I would say a jail facility is not the appropriate place to treat someone’s mental illness.”

The three biggest mental health centers in America are LA County, Cook County, Ill. (Chicago) and New York City’s Rikers Island jail.

Across the country decades of policies affecting those with a mental illness never addressed a replacement for community-based mental health care and supportive services.

Many of the nation’s asylums and hospitals were closed over the past 60-plus years.

“Local jails and prisons have become the de facto mental health institutions,” says Elizabeth Hancq, director of research at the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit that works to eliminate barriers to treatment for people with severe mental illness. “It’s really a humanitarian crisis that if you suffer from a severe mental illness in this country, you almost need to commit a crime in order to get into the system.”

Almost one-third of people with a mental illness get into treatment systems through an encounter with a police officer, according to the first-ever national survey of sheriffs’ offices and police departments on these issues.

Thousands of people who’ve been declared incompetent to stand trial and who need mental health treatment are in jails for unconstitutionally long periods before they are convicted or even tried for any crime, according to a report by The Atlantic.

Even brief jail stays for low-risk individuals with a mental illness can more than double recidivism rates, according to a University of Michigan study.

“It demolishes them,” says Steve Leifman, a judge with Miami-Dade County’s 11th Judicial Circuit.

“I don’t know how anybody gets well in there,” says LA’s District Attorney Jackie Lacey, who has supported efforts to find alternatives to the Twin Towers.

Over the years, the Los Angeles County jail has been forced to address the treatment and reduce the criminalization of people living with a mental illness. Most action was spurred by lawsuits and subsequent court settlements.

On a recent morning LA Superior Court Judge Karla Kerlin is thankful for the day’s relatively light load — just three dozen files on her desk. On some days the stack obstructs her courtroom view. Kerlin oversees the city of LA’s diversion and reentry housing court.

At a large house in a central LA neighborhood, some of the 22 men who live here are watching TV or just hanging out.

Nearly 80% of the people in this diversion and housing program are living with at least one serious mental health disorder. About 40% have both mental health and substance abuse disorders.

At age 16, Finn says, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. “I saw a lot of different visual hallucinations that really affected my day to day life. My head wouldn’t stop shaking. My head doesn’t shake anymore, thank God, because of the medication they have me on.”

Finn is getting, in the words of the court, “restored” to mental competency here instead of in a jail or a state hospital. If he continues to make progress, his pending criminal case will be dropped.

“I don’t go through the suicidal thoughts that I used to,” Finn says. “I don’t go through voices as much. Like, I’m in a very good headspace,” he says adding, “better than jail.”