Behind wrought-iron gates, beneath a polished granite slab, James Ambrose Johnson Jr. whiles away eternity in Buffalo. His earthly life ended in 2004, in Los Angeles, after 56 years, but Johnson returned for posterity to his hometown, to the city of his angry youth. That anger, Johnson long ago said, was fed by tributaries global (“I was angry about the poor people in Ethiopia”), national (“I was angry about the politics of the country”) and, most notably here, local: “I was angry that the Buffalo Bills were losing.”

Johnson rose to fame as an R&B artist whose stage name, Rick James, gets top billing on his headstone at Buffalo’s Forest Lawn Cemetery, etched in larger font above his real name, so that Johnson appears to be opening for his alter ego in the afterlife. In 2020, Bills receiver Stefon Diggs paid homage to the “Super Freak” singer by wearing on his cleats a portrait of the same Rick James, as Dave Chappelle played him on Chappelle’s Show. Diggs had learned that the real-life Rick James was a Buffalonian and a Bills fan from a local dentist who was capping one of Diggs’s teeth following a root canal. This was the Buffalo way, finding higher purpose in pain, the Bills and their fans raising one another up in the self-styled “City of Good Neighbors.”

That nickname never got much traction outside of Buffalo, whose Good Neighbors are now better known to the world by another handle, one that embraces the same virtues of small-town civic connectivity through cold-weather football. That new name, Bills Mafia, is barely 12 years old, but it feels ancient, timeless and eternal, with an origin story that is downright Biblical.

In the beginning, there was Adam and Steve. On Nov. 28, 2010, Bills receiver Stevie Johnson dropped what would have been a game-winning touchdown pass in overtime against the Steelers, triggering a public crisis of faith. “I PRAISE YOU 24/7!!!!!!” Johnson later tweeted to God. “AND THIS IS HOW YOU DO ME!!!!!” Nearly a day later, a Buffalo web developer named Del Reid noticed that ESPN’s Adam Schefter had retweeted Johnson’s already-viral outburst. In Reid’s opinion, Schefter was late to the news, his RT needlessly extending Johnson’s misery. And so, like other Bills fans, he tweeted a benign bit of mockery at the NFL insider … who promptly blocked him. “It seemed like a gross overreaction,” says Reid. But Reid didn’t dwell on it. Life and Twitter moved on.

Months later, Reid was at his parents’ house, in Tonawanda. He had grown up in that Buffalo suburb as a Bills fan, an impressionable teen when the team lost four consecutive Super Bowls, from 1991 through ’94. “A lot of Catholic families have a picture of the pope on their wall,” he says. “We had a picture of O.J. Simpson.” After an awkward silence, Reid adds: “It came down in ’94. We’re not monsters.”

Reid left his childhood home that night for Fratelli’s, a local pizza joint, to pick up a takeout pie. Arriving 20 minutes early, he did what he does too often: pulled out his phone. He idly tweeted out the Twitter handles of some friends and fellow Bills fans—all of them Schefter block-ees—in a custom known in those early days of the bird app as Follow Friday. At the pizza counter, without much in the way of thought, the then 35-year-old father of two young girls added a hashtag to his football family. He called them, without really thinking about it, #BillsMafia.

This was April the twenty-second, in the year of our Lord two thousand and eleven. Reid’s coinage, Bills Mafia, received, he says, “a few laughs” from his small group of friends. He picked up his pizza and left.

When Nick Barnett signed with Buffalo as a free-agent linebacker in 2011, after eight years with the Packers, he noticed the Bills Mafia hashtag, which Reid and his buddies—he calls them the “cofounders” of Bills Mafia—had continued to use. Bills fans, hungry for football after that summer’s NFL lockout, were congregating on Twitter in great numbers. So Barnett embraced the hashtag, and not just online. He had the phrase printed on his mouthguard, literally spreading the idea by word of mouth. Stevie Johnson, whose Old Testament crisis of faith had started the whole mishegoss, began embracing the Mafia name, too. And Bills running back Fred Jackson. As a phrase, “Bills Mafia” gained traction the way that companies go bankrupt: gradually, and then suddenly.

As a concept, however—as an ethos—Bills Mafia had not yet coalesced. Reid was working at the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, in web development, upstream from the medical professionals giving hands-on care to patients. He also attended a men’s Bible study group that focused on male accountability. He likes to quote the overlapping wisdom of the gospel writer Luke (“To whom much is given much is required”) and Spider-Man’s Uncle Ben (“With great power comes great responsibility”). Now that Bills Mafia was gaining traction as a happy epithet, one of Reid’s original “cofounders” asked: “Should we do something with this?”

Abby Curtis

“We were absolutely not looking to monetize it,” says Reid, who created some Bills Mafia T-shirts that mashed up the Twitter and Bills logos and approached the development office at his hospital, asking whether they’d like to become the beneficiary of a Bills Mafia shirt sale. “It was a very confusing conversation,” he recalls, “because they didn’t understand this combination of the Bills, Twitter and the word Mafia.” Finally, Reid says, he asked more directly: “Can I just give you money?”

From that seed he started a one-year community service project, with a goal of producing a different T-shirt every fortnight. An ORCHARD PARK shirt would echo the Jurassic Park logo, with a buffalo in place of the T-Rex. A Seussian shirt reading BLUE CHEESE AND WINGS would offer a sly homage to the cover of “Green Eggs and Ham.” Each would be created by a different Buffalo-adjacent artist, with proceeds going to a different family in need, beginning with a Bills fan whose daughter had eye cancer. Eventually, in 2015, Reid was laid off and urged to apply for another role within the hospital—but, as he explained over the phone to his wife, Chrissy, he had something more ambitious and less secure in mind: to turn the Bills Mafia into a full-time, philanthropic calling through a nonprofit he would name 26 Shirts. Chrissy, at the time, was in Manhattan, visiting the 9/11 Memorial, and thus open to the idea of making the world a more hospitable place.

“So from the jump we have tried to associate Bills Mafia with giving back and charity,” Del Reid says.

“Later, Bills Mafia became associated with people jumping through tables. And look: People can celebrate their fandom in their own way; I’m not here to pooh-pooh anybody. Just please be safe. … But for a while, it was just the tailgate antics that were the focus.”

Those tailgating antics are certainly part of the Mafia’s global brand. Table-slamming involves throwing oneself—or perhaps a close friend—onto a Lifetime brand fold-in-half church-banquet table, usually on video, to be instantly posted for likes and lolz. Sure, the occasional knucklehead has been slammed onto a burning table and engulfed in flames. And yes, Simpson, the disgraced former Bills running back, did attend a home game last winter and found fans eager to pose for photos with him, including one guy in a Rumple Minze hoodie, and another gentleman wearing a novelty trucker hat with plastic bird poop on the bill, its crown emblazoned DAMN SEAGULLS. But these are not the bulk of the Bills Mafia, whose tailgates are a welcoming combination of cosplay and communal drinking. Comic Con meets Omicron.

Infiltrating the Bills Mafia at the 50-year-old venue now called Highmark Stadium, the neutral observer feels like a real-life mob informant. The man not wearing Zubaz, a Steve Tasker jersey, face paint and a horned helmet from the Loyal Order of Water Buffaloes risks looking conspicuous, especially if he’s not two-fisting tallboys of Labatt Blue Light at 9 on a Sunday morning. When a man emerges from a port-a-potty in Lot 7 wearing a full Bills uniform, replete with visored helmet, it’s the guy he holds the door for—in khakis and a quarter-zip—who appears to be attending a costume party.

In a private parking lot across the street from Highmark, 65-year-old Ken Johnson is soberly dressed and soberly comported. “My costume is a hat,” says the gray-bearded Johnson, better known to the Bills Mafia as Pinto Ron because he grills on the hood of his 1980 Ford Pinto wagon and 25 years ago was misidentified as “Ron” in an Athlon Sports NFL preview magazine.

Vincent Alban

Pinto Ron, a Rochester software engineer, says he has attended every Bills home game since 1984, and every Bills game period—463 straight, home and away—dating back to ’94, excluding the COVID-19 contests that were closed to the public. In Orchard Park, he cohosts the joyous pregame tailgate at the private parking area known as Hammer’s Lot, whose tough-but-fair owner, Eric “Hammer” Matwijow, firmly prohibits, as his sign says, “funnels, dizzy bats [and] table slamming.” (A dizzy bat, for the uninebriated, is a Wiffle ball bat filled with beer and weaponized in a vertiginous drinking game.)

Instead, drinks in Hammer’s Lot are largely dispensed from the thumbhole of a bowling ball that Pinto Ron long ago liberated from a stranger’s curb. The son of a Buffalo truck driver whose family of six lived in a 10-by-55-foot trailer, Pinto Ron grew up in poverty, and so Trash Day treasure hunting is rooted in his childhood. “The big trip of the year was going to McDonald’s,” says Pinto Ron, whose craving for grilled meats has occasioned a slight overcorrection in adulthood.

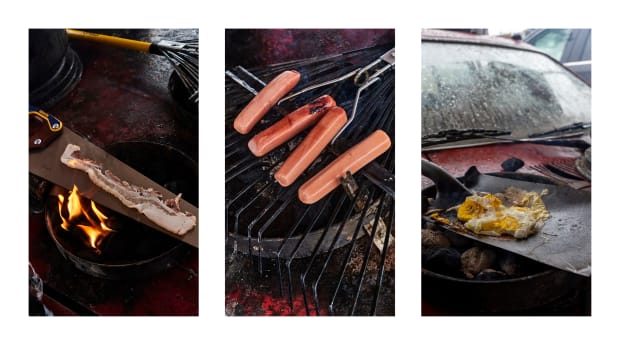

Today, on the hood of his street-legal Pinto, he has “six main grills” going. He’s cooking chicken wings inside of an Army helmet, cocktail wieners in a hubcap, hamburgers and hot dogs on a rake, bacon on a handsaw, a breakfast menu—pancakes, eggs and omelets—in a shovel, and ribs and shish kebabs in the wheel rim of the auto racer Colton Herta’s Indy car. (Long story.)

Parked next to Pinto Ron, operating out of an off-white 2002 Dodge Ram van, his pal Pizza Pete is making pies inside of a filing cabinet, jerk chicken inside of a rusted mailbox, Italian wedding soup inside of a watering can inside of a wheelbarrow, and pulled pork in the oil pan of a Buick Regal.

In the 1980s, Pinto Ron—back then still d/b/a Ken Johnson—and his buddies would end their meaty Bills tailgates by setting up their empty beer bottles like tenpins and knocking them down with the aforementioned bowling ball. In ’89, at a Rochester bar called Marge’s, he drank a shot of the house specialty, Wiśniówka, on a dare. The Polish cherry liqueur tastes “like 100-proof NyQuil,” Pinto Ron says. “Naturally, I went running around to every liquor store in Polish neighborhoods and got some for the next tailgate.” When his shot glass shattered at a game sometime in the ’90s, the bowling ball became the obvious new dispenser of Wiśniówka.

From left: Clay Patrick McBridge/Sports Illustrated (2), Ariana Shchuka

And so: Two and a half hours before the Bills and Vikings kick off in November, with a needle-like snow slanting down, a 40-year-old woman takes the bowling ball in both hands, does a shot from the thumbhole, drops the ball, pulls an antiseptic baby wipe from a pouch and cleans her lips, perhaps unnecessarily. The liqueur, at 71% alcohol by volume, is practically its own disinfectant, Pinto Ron insists. “One hundred proof will sterilize almost anything.”

By now a crowd has gathered around Pinto Ron, hundreds of Bills and Vikings fans jockeying for position around the Pinto where—90 minutes before kickoff, by longstanding custom—he will be doused in ketchup and mustard, dozens of squeeze bottles aimed at him as if he were facing a fast-food firing squad.

It’s a ritual that dates back to the time his brother Frank, out of sheer laziness, shot a perfect dollop of ketchup onto Pinto Ron’s waiting hamburger roll from five feet away, rather than walk all the way over there. Now, revelers massed five-deep on the berm behind the Pinto have cameras poised in their trembling hands. “They won’t be able to see anything,” says Pinto Ron, who’s slightly burdened by his attendance streak and his litany of ridiculous rituals. In three days he will be in Toronto, shooting a commercial for Mailchimp in which he’ll be doused with ketchup and mustard for five consecutive hours, breaking only for lunch and the occasional hosing down. “You do something stupid long enough,” he sighs, “you become known for it.”

It can be burdensome. Heavy lies the head crowned in ketchup. Pinto Ron had open-heart surgery in February 2021 to repair a heart valve. “Last year I pushed myself too hard during the season, and it definitely affected my recovery,” he says. Over the last three games of this regular season—for the first time in 30 years, outside of the height of COVID-19, when large gatherings were discouraged—he suspended the condiment ritual. “The ketchup ceremony in the cold, and the 20 minutes or so of selfies after, takes a large toll on me,” he says.

And besides, Bills Mafia has so much more to offer than spectacles on social media. “We had been taking on this image of table-crashing, this negative image of stupid Buffalo things,” says Pinto Ron. “Then the charity stuff took over. Now it overshadows the table-crashing.”

Abby Curtis

When the Bengals beat the Ravens in the final week of the 2017 regular season, sending Buffalo to the playoffs for the first time in 17 years, the Bills Mafia returned the favor. In a happy, spontaneous wildfire on social media, Buffalo fans began donating to the Andy & JJ Dalton Foundation, which fundraises for “seriously ill and physically challenged children.” Andy (then the Bengals’ quarterback) and the foundation he started with his wife were flooded with donations. “I sent 17 dollars; I can tell you that,” says Pinto Ron. And he was hardly alone: The Bills Mafia donated more than $442,000.

Three seasons later, when 80-year-old Patricia Allen died just before her grandson Josh led the Bills to a Week 9 win over the Seahawks, the Bills Mafia raised a million dollars for Oishei Children’s Hospital in Buffalo. Again, many of the donations came in $17 increments, for the Bills quarterback’s uniform number.

After Baltimore quarterback Lamar Jackson was concussed against Buffalo last season, the Bills Mafia donated another half a million dollars to Jackson’s favorite charity, Blessings in a Backpack, which provides food for children when they’re not in school. “Bills Mafia showed amazing generosity by helping so many kids in need,” the QB said. But the truth is: Almost any worthy cause might benefit. Mafia munificence is now an ever-sweeping searchlight; no one really knows where its beam may fall next. Example: Feeling robbed by the referees in a six-point loss to the Buccaneers last year, the Bills Mafia raised $65,000 for a charity called Visually Impaired Advancement.

By the time Bills superfan Ezra Castro—known as Pancho Billa, for his signature sombrero and leather luchador mask—died of cancer in 2019, fellow fans had raised more than $60,000 for his family. (The PANCHO POWER T-shirt produced by 26shirts proved so popular that it remains available in perpetuity.) When Buffalo briefly disappeared beneath seven feet of snow this past November, Good Neighbors took shovels in hand and dug out the driveways and sidewalks of Bills players and coaches, allowing them to get to the airport for their game, which had been relocated to Detroit. The Bills Mafia had done the same thing in ’14, when ski-masked strangers on snowmobiles picked up players in front of their homes and conveyed them, like sacks of Christmas toys in Santa’s sleigh, to the practice facility in Orchard Park. And in December, when another blizzard killed at least 42 people in Erie County, Buffalonians continued to draw from their bottomless well of empathy.

When Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa was concussed against the Bills in September, and showed alarming difficulty walking to the huddle, more than 1,000 Buffalo fans donated to the Tua Foundation for youth initiatives. After the teams met again, in Buffalo in December, Tagovailoa gave a postgame “shout-out to the Bills Mafia.” He hadn’t forgotten their generosity and concern. “I really appreciate that,” he said.

And then came the horror in Cincinnati. Bills safety Damar Hamlin went into cardiac arrest Jan. 2, on Monday Night Football. As players wept and the game against the Bengals was abandoned, fans—strangers to Hamlin and one another—found the GoFundMe page that the 24-year-old had set up in 2020 with the meager goal of $2,500 for a Christmas toy drive in his native Pennsylvania. Within days, the Chasing M’s Community Toy Drive had received $8 million in donations, a patchwork quilt of 10s and 20s, and larger sums ending in 3 (Hamlin’s uniform number), like Colts owner Jim Irsay’s contribution of $25,003.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

“If you get a chance to show some love today, do it!” Hamlin had tweeted, apropos of nothing, in 2021. “It won’t cost you nothing.” Now Del Reid and 26 Shirts did what they do: They made a new T-shirt. SHOW LOVE—IT COSTS NOTHING, it read, and proceeds went to Hamlin’s toy drive. “Typically we try to bring families into the spotlight, as opposed to walking towards an existing spotlight,” Reid tweeted. “But Damar’s situation is the intersection of who we are and what we do.”

A second T-shirt—a bengal tiger and buffalo embracing—benefited the University of Cincinnati Trauma Center where Hamlin was treated. (Hamlin, too, is selling a T-shirt to benefit the trauma center. He also announced this week that he’d direct some of the $8.6 million from the toy drive to help support young people through education and sports.)

All this largesse is “just an expression of who we are as a community,” says Reid, “both in western New York and around the world through the Buffalo diaspora.”

The Bills Mafia is a global family, but that family is rooted Up Here, in the 30th row of the third deck of Highmark, where the game arrives as a rumor, carried on the shifting winds off Lake Erie. In 2026 the Bills will move into a new billion-dollar stadium, with roughly 60% of its seats covered, but for now we sit on metal bleachers, wet from snow, using a La Nova pizza box as a seat cushion.

“My wife’s afraid of heights,” says the red-bearded guy to my left, summiting the snow-capped peak of Section 333 to take in that November game against Minnesota. “I can’t believe I got her Up Here—except that tickets Down There are $800.” To my right is a grandfather wearing a hooded snowmobile suit that exposes only his eyes. “You know what a small town this is?” he asks through a slot in his camouflage suit of armor. “I saw Jim Kelly and John Murphy this morning, just walking through the parking lot.” Kelly, of course, is the Bills’ Hall of Fame former quarterback, Murphy the voice of the Bills on Buffalo’s WGR-AM. (Murphy suffered a stroke earlier this month. Within days someone on Bills Reddit had posted “Let’s do what we do, Mafia,” and linked to a donation site.)

Abby Curtis

Overnight, the weather had turned from unseasonably warm to unreasonably cold. As if cued by the Bills’ game-ops crew, snow first began to fall when the parking lots opened at 9 a.m. The weather made a prophet of the meteorologist who promised on Saturday night that the Vikings would be welcomed by “stinging ice pellets,” “blustery winds” and “that battleship gray sky we’re used to this time of year.” And while the stinging, blustery, battle-ready weather is actively hostile, even confrontational, the Bills Mafia is neither of those things.

Beneath that darkening sky, an aging Vikings fan in a horned helmet turns to the rest of Section 333 and screams, “In Minneapolis, we call this a sunny day!” But the Vikings play indoors, at U.S. Bank Stadium. Before that, they played beneath a Teflon dome. “You know what we used to call the Metrodome?” asks Snowmobile Suit Guy. “We called it The Pussydome.” But he says it softly, confidentially, so as not to be overheard by the women, children and Vikings fans in our midst.

Concerned friends, knowing that you’re at the Bills game, will text to ask whether you’ve been thrown through a table yet, or been hit by an airborne sex toy (as one was lobbed into the end zone during a 2018 game), or done a shot of Polish cherry liqueur from the thumbhole of a bowling ball. Buffalo has been fighting disparaging national stereotypes for at least 150 years. Mark Twain had been a Buffalonian for just 20 months when he wrote to a friend, in 1871: “I have come at last to loathe Buffalo so bitterly (always hated it) that yesterday I advertised our dwelling house for sale.”

Ninety-eight years later, the greatest sports columnist of the 20th century deemed the city unworthy of Simpson, the Heisman-winning USC running back. “What do you endorse in Buffalo?” Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times asked his suntanned readers. “A snow shovel? A ball bearing? An overshoe?”

When Pat Phillips was the head golf pro at Tan Tara Golf Club in North Tonawanda, the club’s Texas-based management company wanted to know what Phillips could do in September and October to get more people out on the course. “What happens after Labor Day,” Phillips, now 57, patiently explained, “is bowling season starts. People bowl here.” Phillips hates bowling, but he joined a Monday-night league, anyway, out of civic duty.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

The other thing Buffalonians do in the fall is watch the Bills. “Mondays after victories are great; Mondays after defeats, people are down in the dumps,” says Phillips, who helped tear down a goalpost after a home win in the 1990s. “When the weather starts getting like this, it can get depressing. The Bills—and the Sabres, too—are a shot in the arm. They get people through the winter.”

This is also true of our metaphorical winters. When Phillips was diagnosed with Stage IV kidney cancer, in 2014, he and his wife, Michelle, were raising three teenage boys. Pat’s doctor said that he’d typically seen patients live 11 months to two years under similar circumstances. “Good thing he was wrong,” Pat says today, eight long football seasons after his left kidney and a massive tumor were removed.

Among the first Buffalonians to rally to the aid of the Phillips family were Del Reid and 26 Shirts, who made a tee for Pat that read BUFFALO WILLIAMS, a play on the Bills and their many players at the time with that surname. “It was a great thing,” says Phillips. “Not just the money [raised], but to know someone is looking out for you. That’s the biggest thing about the Bills Mafia, what the Buffalo community is all about: If you’re in need, people rush to help you. We don’t know any different.”

Perhaps because they’ve been collectively reduced to snowbound, Super Bowl–losing gobblers of beef on weck, Buffalonians have historically been alive to one another’s pain. They’re “so empathetic,” says Sherry Brinser-Day, from the city’s north side. “They get the working man, down on his luck, and connect with that. People here know. Our reputation is more than the economic downfall that we had; it’s more than the blizzard of ’77. But those things also made us who we are.”

Buffalo is more than wings, Wide Right and table-slamming. Buffalo is more than the Bills and bowling and roller derby, the sport that Brinser-Day took up at age 46 when she joined the Nickel City Renegade Roller Derby, competing first as Sherry Bomb and later as All-Fight Knocks, a play on Buffalo’s venerable art museum, Albright-Knox.

She joined the league at Kiddy Skateland, on the north side of Buffalo, during the two years when her husband, Tim, was waiting for a heart transplant. Tim was a cop in Tonawanda—Officer Day worked nights—when, at age 45, he had what he thought was a heart attack but turned out to be, after agonizing months in the hospital, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES), in which white blood cells attack internal organs. The Day children were 4, 5 and 7 years old at the time, kissing their father goodbye for weeks on end.

Abby Curtis

Ultimately, a left ventricular assist device kept Tim alive; and so, in a way, did the Bills Mafia. At the time, Day knew, as all Buffalonians did, that a nonprofit called Wings Flights of Hope was flying Jim Kelly to and from his jaw-cancer treatments at Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospital in New York City. Tim contacted the organization, and soon Wings was flying him to Boston for his own life-saving treatments in the Mass General transplant program. He also saw, on the Buffalo news, that a local boy with brain cancer had benefited from one of Del Reid’s T-shirts. When Sherry met Chrissy Reid, Del’s wife, at the elementary school that their daughters both attended, Chrissy told Sherry: “We’re gonna do a shirt for you.” And so the Bills Mafia searchlight fell on the Days.

“Twenty-six shirts became a vehicle to share our story,” Sherry says. The Days began to see people wearing “their” shirts—a bison in a Bills uniform, based on a 1960s soda pop ad—around their Kenmore neighborhood. A niece in Boston spotted one of the shirts in a bar, and the guy wearing it said, “Oh, yeah, we bought it specifically to support your uncle.” Strangers approached Tim Day at his local Wegmans—the beloved Buffalo-based grocery chain, purveyors of Bills Mafia Wing Sauce—and told him they were praying for him.

More than seven years after he finally got his heart transplant, 55-year-old Tim Day now coaches his teenage son in hockey. He’s able to walk the dog. He and Sherry have bought plenty of T-shirts to support other Buffalonians in need. “Being good to your fellow man, caring about each other, helping each other … we need to do that,” says Sherry. More important than money (which can be anywhere from a few hundred bucks to $13,000 for any given 26 Shirts beneficiary), Del Reid has delivered love, compassion and concern to his fellow Bills fans. He embodies, Sherry says, “the kindness and empathy that all Buffalonians understand so deeply. Del is representing our humanity.”

Del Reid doesn’t want credit for that. He’ll scarcely take credit for his own coinage, Bills Mafia, which is now in the world’s water supply. It’s everywhere in Buffalo and beyond: on sweatshirts, in commercials, affixed to car bumpers—the all-encompassing epithet for Bills fans and Buffalonians everywhere. On a building in downtown Buffalo, there’s a four-story mural painted in Bills blue that says KEEP BUFFALO A SECRET. But it’s getting to be too late for that. On the Sunday morning in November before the Bills visited the Jets, Reid woke up to text messages informing him that the Bills Mafia had been name-dropped in a Saturday Night Live sketch. “The dragon’s awake now,” Reid says of his creation. “Like Smaug.”

If you go looking for the birthplace of that dragon—the old Fratelli’s pizzeria, at the corner of Sheridan and Loretta in Tonawanda—bear in mind that it’s now an Italian restaurant called Romeo and Juliet’s. But the building deserves landmark status, a place in local lore alongside the Anchor Bar, birthplace of Buffalo wings, another creation that started here and was bequeathed to the wider world.

Rick James, another one of those global exports, is gone, but Buffalonians are still making music. Jeremie Pennick, the local rapper who performs as Benny the Butcher, has a song that plays during games at Highmark Stadium. “Bills Mafia Anthem” goes: “[When] we say Mafia, that means family to me.”

The eccentric uncle of that family, Pinto Ron, reserves parking spots for visiting fans at every tailgate in Hammer’s Lot. He says the conviviality of Bills supporters has ever been thus. “Bills Mafia has always been here,” he says of western New York and its émigrés worldwide. “It just never had a name. Now, it’s got a name. Del Reid did that.”

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Like William Shakespeare, Reid has made a permanent contribution to the English language. He and Chrissy have two daughters, Delaney and Chloe, in addition to Bills Mafia, another offspring conceived of love. “Bills Mafia is a celebration of our team, our love, and it’s pure,” Del says. “Any time you’re thinking of margins—money and profit—that ruins things. It takes the purity out of it. Looking back: My ‘cofounders’ and I, none of us were looking to do anything but enjoy our Bills fandom. That’s one of the reasons [‘Bills Mafia’] stuck around so long before [the team itself] adopted it. They saw that it wasn’t being exploited. I’ve been protective of it.”

Look at them now. Del Reid and 26 Shirts have raised more than $1.6 million for Bills fans in need. Meanwhile, his other brainchild, the Bills Mafia, “grew up and left the house and belongs to all Bills fans,” he says, watching in wonder as his intangible invention travels the world. “It’s really cool to be a footnote on my favorite football team’s Wikipedia page. That’s enough for me.”