The massive tax overhaul passed by the Senate early Saturday morning will if enacted into law impact millions of Americans in different ways.

By and large, the most costly provision continues to be reducing the corporate tax rate to 20 percent. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) gives that a $1.4 trillion price tag. Republican claims the measure would pay for itself were also debunked this week by the JCT. Their analysis estimated the bill would grow the economy by .8 percent over a decade, still adding $1 trillion to the deficit.

When it comes to individual income taxes, the Senate measure also makes broad cuts across income levels. However, most of the individual income tax provisions will sunset after 2025 unless Congress acts. The bill also includes a change to inflation adjustments that would raise taxes slightly compared to what they would have been under current law.

By 2027, every income group under $75,0000 is expected to see tax increases according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.

The corporate rate cut, from 35 percent to 20 percent, will be permanent.

The Senate bill is not the final word.

The Senate and House versions of tax reform have big differences including the treatment of the health insurance mandate penalties, as well as the number of tax brackets. The two will need to be reconciled before they get to President Trump’s desk.

Here’s how the Senate plan could affect you:

2017 rates versus your rate under the Senate bill

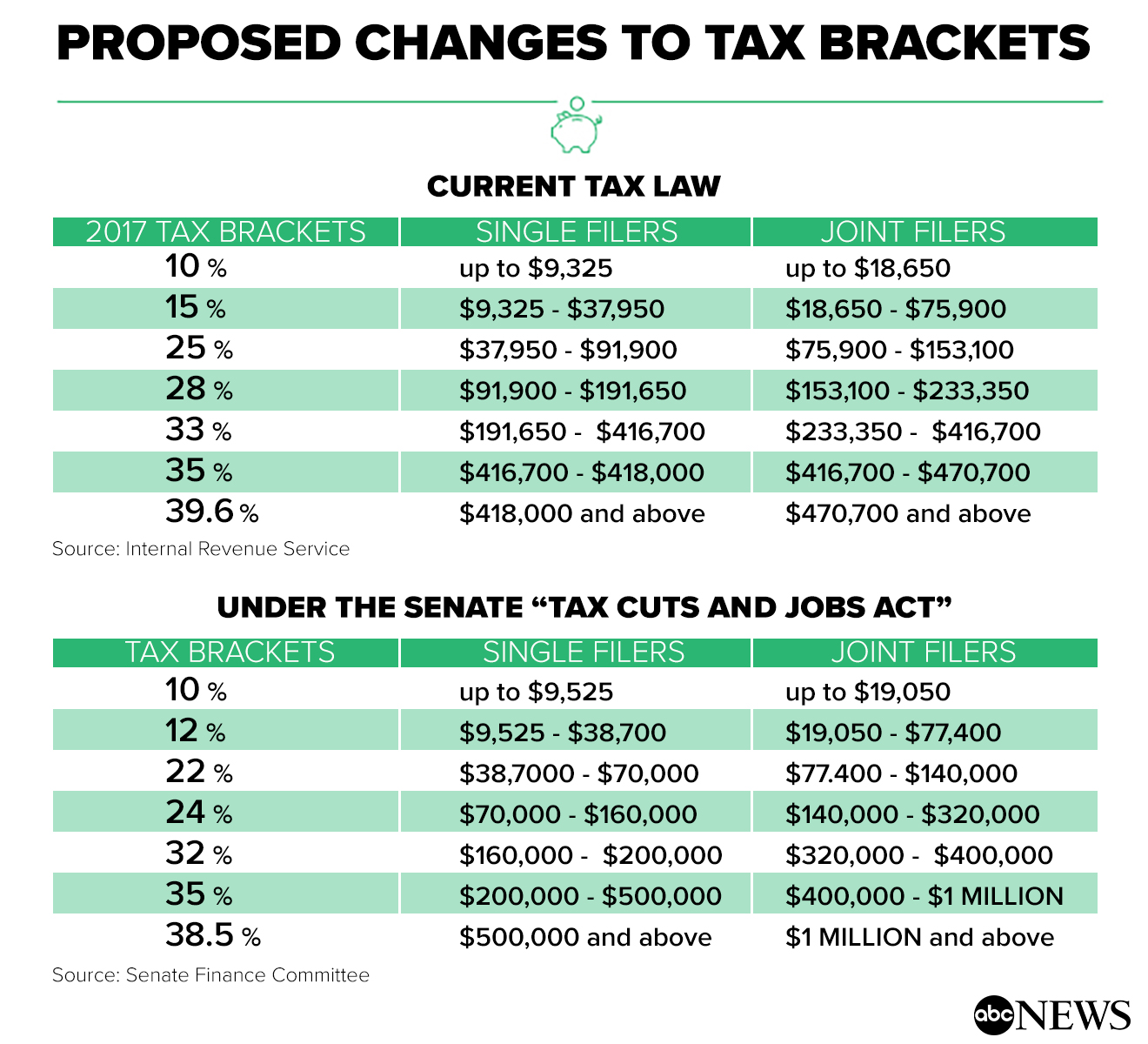

The Senate bill maintains seven brackets, the same number as exist under current law, but it also lowers most of the rates and raises many of the income thresholds. For example, a married couple making $200,000 in 2017 would have paid $42,884.50 in taxes. Under the Senate bill, they would move from the 28 percent to the 24 percent tax bracket, and their tax bill would drop to $37,079 — before deductions are considered.

Standard deduction goes up, other deductions out

The Senate bill would nearly double the standard deduction.

For individuals, it would go from $6,350 to $12,000. For married joint filers, it raises that deduction from $12,700 to $24,000. This may result in fewer taxpayers itemizing their deductions, and the bill’s supporters hope that standard deduction increase will help offset the elimination of other deductions.

“Generally speaking, if you are a taxpayer that takes the standard deduction currently … good chances are you get a tax cut,” said Scott Greenberg, a senior analyst at the Tax Foundation. “Taxpayers with large amounts of itemized deductions, some of them could see a modest tax increase.”

“Lawmakers are trying to create a tax code where fewer taxpayers use deductions that are related to specific economic activities and more taxpayers use the standard deduction,” Greenberg said.

Who takes a hit? In the first eight years, Greenberg says the potential losers are generally people who make great use of tax preferences rather than taking the standard deduction. A few stand out.

People living in high-tax cities and states

People living in high-tax cities and states like New York and California will take a hit, though Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, lessened that blow in the final hours of negotiations by retaining some deductions for property taxes.

The original bill completely eliminated the deduction for state and local taxes (SALT), but Collins insisted on retaining a deduction on property taxes up to $10,000. According to the Tax Foundation, the property tax deduction accounts for just over one-third of all state and local taxes deducted in 2015, the most recent year for which data are available.

According to that group’s analysis, this deduction also benefits middle-income earners more than deductions on state and local income tax would. In Westchester County, New York, the property tax deduction alone is worth $5,548 per filer, according to the Tax Foundation.

The Senate tax bill will include my SALT amendment to allow taxpayers to deduct up to $10,000 for state and local property taxes.— Sen. Susan Collins (@SenatorCollins) December 1, 2017

The issue was expected to be a sticking point in the final negotiations reconciling the Senate and House versions.

“It would have been a point of disagreement that they’d have to sort out,” Greenberg said.

Upper-middle income households with a lot of children

Although the bill does expand the child tax credit from $1,000 to $2,000 it also does away with personal exemptions. If you’re in the 25 percent bracket or lower and you have children, Greenberg says “the Senate bill is a good or harmless trade.”

The personal exemption allows individuals to deduct more than $4,000 as a “personal exemption” for themselves, their spouses, and each dependent. Greenberg says this could hit upper-middle income families.

Health insurance consumers on the individual market

The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated that federal budget deficits would be reduced by about $318 billion by eliminating the penalty associated with the individual mandate. Those effects would occur mainly because households are expected to make less use of things like premium tax credits and Medicaid.

Lower enrollment would mean fewer benefits coming from federal coffers. There is concern that eliminating the mandate’s penalties would lead to adverse selection, where young, healthy people choose not to enter the insurance market, and that would lead to higher premiums.

Wins for the wealthy

While in the first eight years after the bill’s passage, the losers are expected to be the people who make use of tax preferences, the measure includes some big wins for millionaires.

“The tax benefit for high-income households as a percentage of their income would be higher than the tax benefits for other income group households as a percentage of their income,” Greenberg said.

The top tax rate for the highest-income Americans drops from 39.6 percent to 38.5 percent. Also, because of the brackets being reorganized, married couples making between $500,000 to $1 million would see their tax rate drop from 39.6 percent to 35 percent.

Wealthy Americans would also see a benefit in the Senate bill’s changes to the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Senate Finance Committee documents say this was done to help simplify the tax code,

Finally, the richest Americans would see a boon in an expansion of exemptions from the estate tax, also called the “death tax”.

Currently, when a person passes away, his or her heirs can receive up to $5.5 million in property and assets tax-free. The Senate bill doubles that amount ($11 million for individuals, $22 million for married couples).