MATAMOROS, MEXICO (Border Report) — Jodi Goodwin held a brisk pace as she pulled a red wagon filled with documents and office supplies and led a group of lawyers on Saturday across the Gateway International Bridge from Brownsville, Texas, to offer legal advice to hundreds of asylum-seeking migrants in Matamoros.

Known as the “abogada,” (lawyer) Goodwin is a familiar and trusted face here. She comes often and she speaks flawless and fast Spanish. And like most everything she does in life: She doesn’t waste any time.

As they marched across the bridge around 8:45 a.m. and headed toward the tent encampment, some of the lucky migrants were eating breakfast. The food is brought over twice a day by various volunteer organizations, like Team Brownsville. But with 600 people living here — and the numbers growing every day as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents release more migrants to this area under a new Trump Administration policy — the free food runs out real fast.

A few mothers with their barefoot tykes sat on a dirty concrete curb staring at Goodwin and her legal army as they filed past.

“Let’s set it up in the back,” Goodwin barked as she organized and briefed the lawyers, many of whom had traveled from Wisconsin and Minnesota to volunteer.

Temperatures were already in the 90s, and sweat immediately began dripping down their awe-struck faces as they looked into the crowd of migrants who suddenly realized who they were and what they came to do.

Within minutes, Goodwin and her group were encircled and questions began flying. Holding plastic folders filled with their immigration paperwork, they waved their documents before the lawyers, asking for help.

Some of the migrants were scheduled to have court hearings within days, and they had no idea what would be asked of them, what to say or how a U.S. federal immigration court proceeding works.

Many of the lawyers were uncertain themselves. That is because since the Trump Administration began implementing a new immigration policy, called Migrant Protection Protocol (MPP) asylum-seekers who were apprehended after July 17 in South Texas, are being released by U.S. federal agents to the streets of Matamoros, Mexico, prior to their hearing dates. Previously, asylum-seekers either were held in U.S. detention facilities until their federal immigration court dates, or they were released with a Notice to Appear in court on their own.

Read a Border Report story on the Matamoros tent encampment here.

This new policy — coupled with a recent Supreme Court ruling that upholds President Donald Trump’s third-country policy, which requires migrants to seek asylum in the first country they reach after leaving their homelands — has many of these legal eagles wondering what kind of advice to give these migrants.

“People are concerned and understandably so as to whether they need to apply for asylum in Mexico first and what kind of coordination or support they’ll receive the Mexican government,” said lawyer Kristen Clarens, of Charlottesville, Virginia, who volunteered Friday and returned on Saturday to follow up with some of her new street clients.

Clarens has volunteered here about a dozen times and returned on Friday to help, just two days after the Supreme Court ruling was announced. The bottom line, she said, is that all of their legal advice could ultimately be moot because these migrants might have to file for asylum with other countries, or even with Mexico, which could take years.

“I’ve never really seen a vibrant network of cross-border work between the Mexican and American attorneys. So, I’m concerned that it will be really difficult for people to apply for asylum here and that the process could take the same amount of time as it does in our country, which can take up to four to five years and often two (years),” Clarens said.

“It’s just confusion, but that is the goal, it seems like,” said Charlene D’Cruz, 53, a lawyer who traveled from Wisconsin with the nonprofit group Lawyers for Good Government.

“The process is constantly changing so probably the most valuable advice is to give them solid information on how to prepare their application to present to the U.S. government whenever they finally have an opportunity to present it,” said Kim Hunter, 51, a lawyer from St. Paul, Minnesota.

“We’re just going to try and give them the best information possible, translate as much as we can of the madness, which we barely even understand,” D’Cruz said.

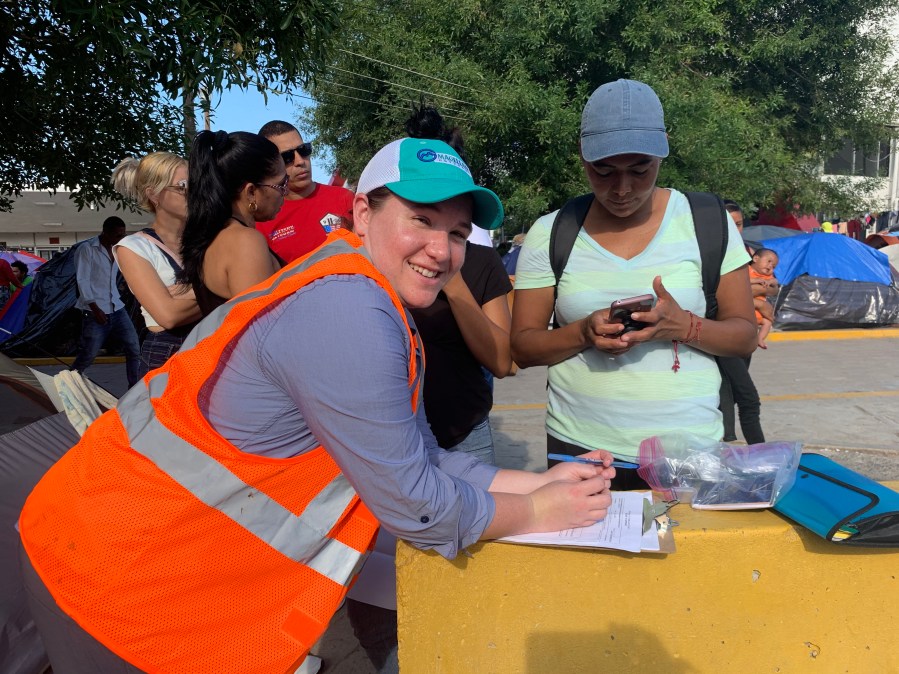

Lawyer Erin Thorn Vela, who works for the Texas Civil Rights Project and who offers these free legal workshops twice a month with Goodwin, says there are more in need of legal advice than they can handle. On Saturday, she was in charge of an in-take line for those who have upcoming immigration hearings and have not filled out any paperwork.

With sweat dripping down from beneath her baseball cap, and her light skin pinking up from the strong sun, Vela asked a line of mostly women the same questions over and over in Spanish. And she helped them write down their answers.

“Ideally they would have done an intake weeks ago,” Vela said as Zulema Calisa showed Vela her Notice to Appear (NTA) on Sept. 30 at a new federal immigration court built at the base of the Gateway International Bridge.

On Thursday, the first cases were heard from the tent facility via videoconference with a federal immigration judge in Harlingen, Texas, about 30 miles away. The second day of these court proceedings were held on Monday.

Calisa has been living in a dirty tent in this encampment for over a month with her 10-year-old son. All around them people are coughing and sneezing. There is trash everywhere and clothes are hung in the trees and on a fence to dry. The smell of sweat and excrement is overpowering and everyone says they are thirsty all the time.

Volunteers deliver water twice a day, but each family gets only one 16-ounce plastic bottle. Mothers with babies must share. And nursing mothers do not get extra.

A barricade was put to deter migrants from refreshing themselves or washing clothes in the nearby Rio Grande. But barefoot children easily walk around it and take each other to the river banks to cool off.

Living here “es super dificil” (extremely difficult) Calisa tells Border Report.

Many migrants have paired up in groups and say they sleep in shifts, fearful that they will get robbed, raped or even have their young children stolen if they are not keeping vigil.

“I don’t know how people could live in these conditions. They’re pretty insufferable conditions,” Clarens said.

Sandra Sanchez can be reached at SSanchez@BorderReport.com.

Visit the BorderReport.com homepage for the latest exclusive stories and breaking news about issues along the United States-Mexico border