AUSTIN (KXAN) — Standing in front of a projector screen with a satellite view map of Weatherford and the surrounding areas superimposed onto it, Bruno Dias stared intently at hundreds of lightning bolt icons.

His face looked the way a weatherman’s does when severe weather is approaching the viewing area, and it’s his job to get the word out before it arrives.

“Lightning strikes kill more people than tornados do, so we need to be proactive about lightning,” said Dias, the Director of Safety and Security for Weatherford ISD.

Like a bullseye with Weatherford at the center, large circles were drawn on the map representing, 10, 15, and 30 miles out from the district, which is one county west of Fort Worth.

“By the time it gets to zero to 10 miles, there’s no one outside,” he said. “If the weather escalates, they’re already positioned and prepared to go into a shelter mode.”

While we came to learn about preventing violence in schools, it’s hard to argue that this is a district that takes all aspects of school safety seriously.

The weather map sat on a side wall inside the district’s security operations center, but it’s an adjacent surveillance apparatus that really grabs attention.

Hundreds of cameras from 11 different campuses and several facilities rotated across four large screens, which are monitored live during school hours.

“We could go live and see, is there a suspicious person, is there someone making demands, what is the situation?” Dias said.

After voters passed a major bond in 2015, the district made significant safety upgrades, including adding all the cameras.

However, the biggest safety changes aren’t physical ones.

After 15 years working in law enforcement in California, Diaz traded his flip flops for cowboy boots and became one of the first to bring the threat assessment screening model to a school campus in Texas.

“We have a screening process with questions, key questions that have been identified by the secret service, by the FBI, in assessing threats, and we see how they answer those questions,” Dias said.

Not every student is screened. Only those whose classmates, parents or teachers report them as having expressed a desire to physically hurt others.

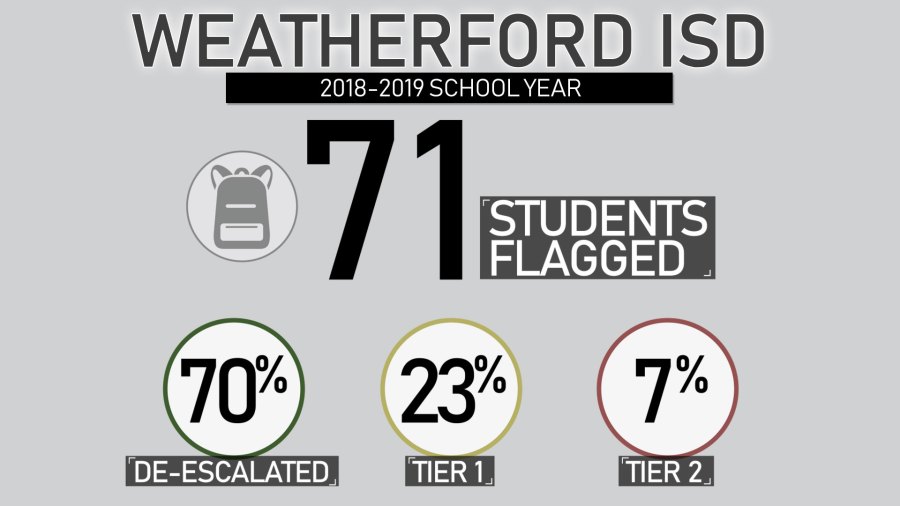

From last December through May, the district conducted threat assessments on 71 of its 8,000 students. The goal is to determine how credible their threat is, and if the student has the means to carry it out.

“It’s an interview. It’s not an interrogation,” Dias said. “During that interview, ‘Do you dislike this teacher?, Why?’”

From there, students are either deemed not a threat, a level one threat, which is less severe, or a level two threat, who is at a heightened risk for carrying out a threat.

“If they start to provide reasons and in that process you ask, ‘Do you really feel about hurting, do you understand what hurting someone truly means?’” Dias said. “That’s what the screening process tries to target. At times people will say, ‘I do, I do know what it means, and I really want to hurt this person.’”

That would be a red flag.

At this point the screening process would become more elaborate, requiring Dias to fill out an 18-page form with questions like:

- How easily can this student access weapons?

- Is there a scheduled attack?

- What is their social status among peers?

- Do they have a mental health diagnosis?

- What kind of family life do they have?

“Based on the information we have, we develop a management strategy,” Dias said.

For the student, that may mean both a counseling and safety plan.

The district would offer more services, including regular counseling sessions, while Dias and his team could add more virtual and physical monitoring along with random searches.

Dias points to early data showing the threat assessment model is working.

Of the 71 students flagged, 70 percent of the potential threats were de-escalated, 23 percent stayed as the lower level “tier one” incidents, while seven percent escalated to tier two.

With so many assessments, Dias admits case management is a problem.

In response, the district is looking at acquiring a database to track progress.

There are also privacy concerns, and while both the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act apply to this type of information, both have safety exemptions that allow for sensitive information to be shared under the right circumstances.

Dias said if there’s the threat of an imminent attack, the exemption allows administrators to share relevant information about the student with law enforcement and other people in the position of being able to prevent the attack.

Statewide Threat Assessment

If this all sounds like a novel experiment, it’ll soon be a reality throughout Texas.

Starting this 2019-2020 school year, every school district in Texas is required to have a similar student threat assessment model in place.

A new state law calls for educators, counselors, law enforcement, mental health experts and other stakeholders to form a committee that conducts student threat assessments. Once the risk level is determined, the districts are then required to support the student and potential targets with additional services.

It’ll be up to the Texas School Safety Center at Texas State University to audit districts and determine which are noncompliant.

Weatherford as an example

Word of what’s going on in Weatherford reached Austin ISD last year when the district’s police department first heard about the threat assessments.

AISD Police Chief Ashley Gonzales is part of the new team that spent much of the summer readying for the new threat assessment protocol.

He explained that having this kind of information on high-risk students could be the difference between de-escalating a potential threat, and getting caught off guard.

“Sometimes those situations can escalate into self-harm or violence against others, and that’s what we’re trying to prevent,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzales said part of the benefit is that when a student switches schools within the district, there won’t be any guessing or reading between the lines when it comes to past disciplinary issues. Instead, the completed threat assessment will be available for administrators to look through.

“We want to make sure that if a student has been identified, that they continue to receive services,” Gonzalez said. Just because they’re moving to another campus of another school, different grade, that doesn’t mean the services stop and that information is not shared.”

In the case of Weatherford ISD, it also passes along the threat assessment to other school districts when a student transfers, if the new district requests it.

Like the threat assessment itself, Dias hopes this type of sharing can serve as a model for how Texas schools interact with each other when it comes to safety and security.

“If I’m a counselor and I’ve developed an effective strategy with this child, I want to make sure that the strategies that I’m employing are going to be handed off to the next counselor so that we can keep that child on a successful pathway,” Dias said.

Whether it’s severe weather or a student hoping to cause harm, if Weatherford ISD is in the bullseye, Dias wants to be prepared before the threat reaches campus.

“We can’t just say, ‘Hey we have cameras for security, but let’s go ahead and forget about weather, forget about lightning,’” Dias said, “It’s a holistic approach, everything is working together.”